Lily Karedada

Lily Karedada was born circa 1935 of Woonambal parents in her father’s country, Woomban-go-wangoorr, near the Prince Regent River in the East Kimberley. Her bush name, Mindindil , means ‘bubbles’. This name referred to the time when her father saw bubbles emerging in the freshwater spring - alluding to his daughter’s spirit coming from the water. As he looked into the spring water on top of a hill, he announced to his wife, “ Ah, what this one here, he comes out bubble? Ah! Might be kid. ”

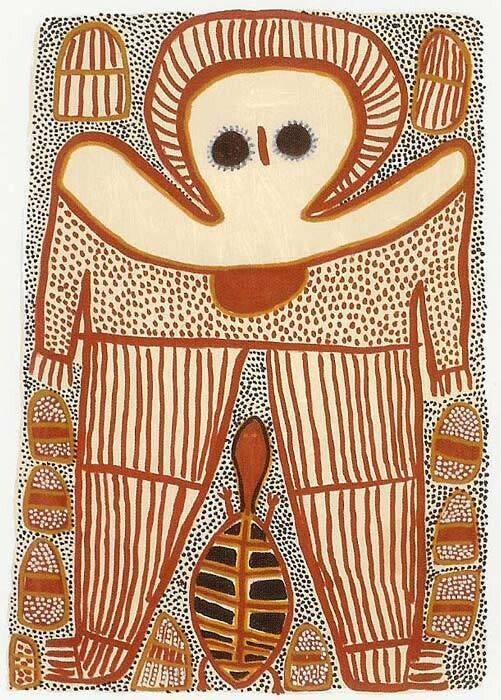

Lily belongs to the Jinnengger (owlet nightjar) moiety and her totems are the turkey, possum and white cockatoo. As a baby, she was carried in a bark coolamon and grew up eating bush tucker such as kangaroo, yams, wild honey, fish and goannas. Her father passed way while she was quite young. During her teens, her family went to country called Giboolday on the Mitchell Plateau. It was here Lily met and married Jack Karedada, with whom she had ten children.

During World War II, Lily and Jack moved to Kalumburu, on the northwest tip of Western Australia, where she helped the nuns at the Mission to plant mango and coconut trees. Here she and Jack would paint, Lily becoming a prolific painter, especially of the Wandjina figures. This remote area of the Kimberley is referred to as ‘Wandjina Country’.

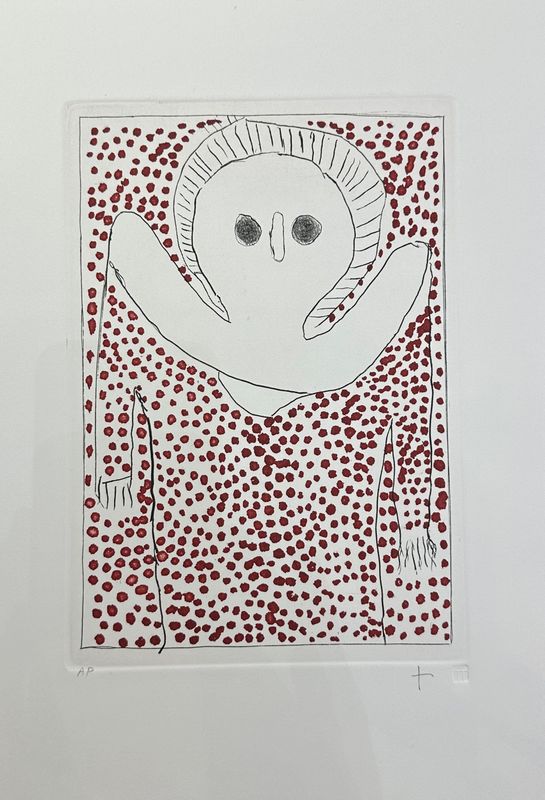

The enigmatic Wandjina figures are seen in the surrounding caves and rock galleries, being maintained by over generations. For the local tribes, the Wandjina ancestor spirits were central to their natural and spiritual world, with each clan group tracing theirs descent from a distinct cave area. It is this region that the much older Bradshaw figures are also found, as well as the Rainbow Serpent.

Many aeons ago (during the Dreamtime), after their creative acts were done, the Wandjina lay down in the caves, leaving their life giving essence in the cave paintings as they returned to their home in the clouds. They are known as rainmakers and bring fertility to the land. They are usually shown either in groups or surrounded by associated totemic species. Always depicted frontally, their large eyes dominate in a mouthless face, sometimes on top of a simple robe-like body, with no apparent limbs or feet. Radiating lines around the eyes or in a halo around the head represent the lightning that heralds the storm. The first lightning strike renders their mouths tightly closed. If their mouths were left open, we are told, it would rain incessantly, carrying everything away in an absolute torrent. Wandjina float vertically on the rock surface or may be shown lying down. They are precious ancient icons, and their contemporary re-representation has allowed for their preservation and the survival of a unique culture.

Author: Sophie Baka

Whilst the earliest copying of these images from rock to bark was at the request of missionaries and explorers during the 1930s, the missionaries were to displaced Lily’s people from their traditional lands. Their way of life, including the regular re-touching of the rock images and conveying of stories by tribal elders was forbidden. Lily still recalls how the hard work routines of their early mission life took all their time and energy.

Kalumburu is now an Aboriginal-run with income being largely derived from art and craft production. The Karedada family have long been recognised as leaders in the Wandjina tradition.

The Wandjina holds a special affinity with the owl, Lily belonging to the Jirrengar owlet moiety. It was said that a sympathetic Wandjina spirit rescued the legendary owl, Dumbi, from a group of playful children who were pulling out its feathers. Though the Wandjina returned to the clouds, a close association remained between the two.

Judith Ryan and Kim Akerman, in the definitive book on Kimberley art “Images of Power”, have described Lily’s style as follows: “ Lily specialises in representations of Wandjina executed in a refined style, full of subtle tonal variations. Sometimes the Wandjina is shown emerging from a veil of dots (rain) which also inundate his body. Both the outlines and the dotting are far more precise than the vigorous gestural marks of sister-in-law Roslyn Karedada. A dotted ground is also characteristic of Lily’s depiction of totemic species and the natural features of her country. ”